Data underscores this directional shift. In 2023, lending technology represented 41% of total FinTech investment in Southeast Asia, up from just 14% in 2020 [1]. Lending has not only captured investor interest — it has become the leading revenue driver in the region’s digital financial services sector. Between 2022 and 2024, digital lending revenue grew 35% to US$22 billion, accounting for 65% of all digital financial services revenue [2]. Forecasts indicate that by 2025, digital lending will surpass payments as the primary contributor to FinTech revenues in the region, with a projected CAGR of 33% [3].

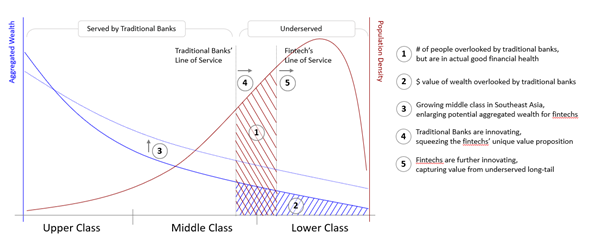

This momentum is propelled by a market that remains deeply underserved. Over 290 million adults in Southeast Asia — or roughly 38% of the adult population — are unbanked with estimated funding gap of US$100 billion for personal loans [4]. The SME funding gap alone stands at an estimated US$300 billion, reflecting longstanding barriers to access for small and micro-enterprises [5].

Meanwhile, digital infrastructure continues to advance rapidly. High internet and smartphone penetration have enabled users to access and demand more sophisticated financial services. Yet traditional credit scoring systems remain inadequate or absent across large parts of the region, limiting banks’ ability to lend confidently.

At the same time, FinTechs that once led with wallets or payments have faced profitability constraints. Thin margins and fierce competition have made it difficult to scale sustainably. In contrast, lending offers stronger fundamentals — recurring and predictable revenue, better unit economics, and higher interest-based yields. For investors and founders alike, these dynamics are difficult to ignore.

To appreciate the opportunity in lending, it helps to understand how traditional retail banks make money — and why they leave gaps for FinTechs to fill.

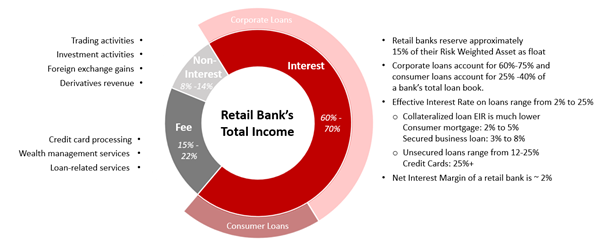

Retail banks primarily generate income through net interest margin (NIM): they accept deposits at low interest rates (typically 2–4%) and lend out at higher effective interest rates (2–25%), depending on the borrower’s profile and collateral [6]. About 60–75% of their loan books are allocated to corporates, while 25–40% goes to consumers. This interest income contributes 60–70% of total revenue for most banks.

Fee-based services, such as credit card processing and wealth management, account for 15–22% of income. Non-interest income — from trading, FX gains, and derivatives — contributes another 8–14%. Over centuries of iteration and evolution, the banking system shaped modern retail banks to borrow from the public at low cost of capital while lending it back out to consumers and enterprises in need at a higher effective interest rate, generating around 2% of NIM and building diversified revenue model around its financial service offering.

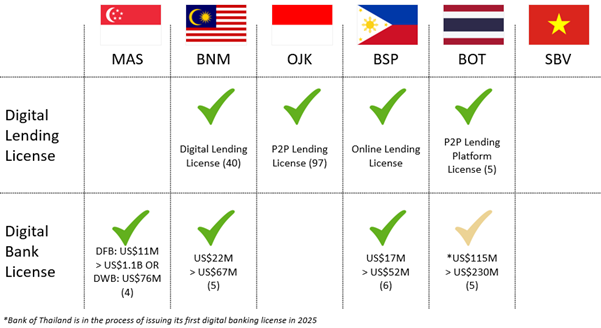

To replicate the business model of traditional banks and emerge as a lender in Southeast Asia, FinTechs have to obtain and operate as a licensed digital lender or a digital bank. Then the FinTech has to compete against fierce competition to emerge as a champion within the finite cage of uncertainties.

While Southeast Asian regulators have made moves to support innovation, FinTechs face an uphill battle to build sustainable lending businesses.

Obtaining a digital bank license requires a rigorous application process, extensive compliance systems (AML/CFT, cybersecurity, governance), and ongoing audits. Even after securing a license, digital banks must maintain capital adequacy ratios, liquidity buffers, and pass regular stress tests — all of which are expensive and operationally demanding.

Digital banking frameworks across the region provide a path for FinTechs, but the bar remains high:

While these frameworks are more flexible than traditional banking regulations, the capital required remains prohibitive for many early-stage startups. As a result, most licenses have gone to consortiums backed by large conglomerates or well-capitalized scale-ups. In the Philippines, only Tonik and UNOBank have emerged as digital banks founded by FinTech startups.

Beyond licensing, FinTech lenders contend with:

Despite these hurdles, startups retain two key competitive advantages: data and agility.

With access to both traditional and alternative data (e.g., behavioral, social, or transaction-level data), FinTechs can build innovative underwriting, risk management, and customer engagement models. Freed from legacy systems, they can implement digital, automated, and lean technology and process structures that reduce costs and scale rapidly.

These strengths enable FinTechs to either disrupt and challenge or collaborate with incumbents — expanding access, lowering costs, and unlocking new business models.

While the digital lending boom in Southeast Asia has so far been shaped largely by consumer-focused platforms, two underpenetrated but high-potential frontiers are emerging as the next engines of growth: B2B financing and proxy-collateralized lending models. Both represent a natural evolution of the FinTech lending landscape — offering better risk-adjusted returns, more defensible moats, and more attractive unit economics compared to traditional unsecured personal lending.

SMEs contribute roughly 42% of Southeast Asia’s GDP but face a funding gap of US$300 billion [11]. Marginalized by traditional underwriting technology and processes, most SMEs — especially those in supply chains, manufacturing, retail distribution, and e-commerce — remain underserved by traditional banks. Up to 66% of SMEs struggle to secure funding, often relying on personal savings or informal loans. Only 23% receive financing from traditional banks, and just 7% from alternative lenders.

Compared to the innovation achieved in consumer financial services over the past decade, business servicing has not evolved as much, leaving potentially even a larger gap of underserved medium and small size enterprises across Southeast Asia.

There are characteristics of business loans that are more attractive to lenders when compared against consumer loans. Business client acquisition tends to be a more sales-oriented activity instead of marketing activity, allowing startups to have better control over its client acquisition process and resources. Business loans tend to be larger in size, resulting in better revenue to cost economics. They also tend to be less price sensitive, and are more likely to generate recurring business.

Business loans tend to carry lower default rates compared to unsecured personal loans due to the lasting and crippling network effect it has on the larger operations, and many times these business loans have added security measure through personal guarantees. Once the FinTech finds suitable business client persona that fits well to its value proposition, business clients can prove to be more reliable sources for building early traction, compared to consumer borrowers.

Additionally, Southeast Asia is at an inflection where SMEs are also going through digital transformation, and FinTechs can now underwrite SMEs more accurately using new data sources. Local governments (e.g., Singapore’s Go Digital program, Malaysia’s SME Digitalisation Grant) have been incentivizing and encouraging SMEs to digitize their operations, become more data driven, and take advantage of digital tools to unlock massive efficiency gains.

Organically, SMEs are integrating with digital payments and e-commerce platforms to keep up with the demand and gradually adopting back-end ERP, CRM, and accounting tools to help automate many administrative tasks. Cloud service usage among ASEAN SMEs reaching USD12 billion. In Singapore, SME tech adoption rose from 73.8% to 94.3% over five years [12] and over 2 million SMEs in Indonesia and 1.5 million in the Philippines have adopted digital platforms to support business operations [13].

Business borrowers present an attractive client opportunity with relatively stronger fundamental for FinTech lenders, ripe for harvest. FinTech can leverage its competitive advantage in data processing to assess risk, tailor products, and integrate directly into SME workflows to provide contextual and integrated B2B credit products while differentiating from traditional lenders.

As FinTechs double down on B2B lending models, a natural next step is to engineer stronger institutional trust in these credit flows. This brings us to the next evolution: how FinTechs are beginning to transform their liability side — not just who they lend to, but how they fund those loans, and at what cost of capital. This is where innovations in collateralization, warehousing, and securitized credit rails come into play.

One of the longstanding challenges in Southeast Asia’s lending sector has been the dominance of unsecured lending, largely due to the lack of formal, liquid collateral — especially among MSMEs and informal workers. However, a new wave of FinTechs is finding ways to replicate the economics of secured lending through proxy-collateralized structures — products that don’t rely on traditional hard assets but still reduce loss likelihood and improve underwriting confidence.

Technology startups are best positioned to experiment and pioneer such innovation because of their competitive advantage in data and agility. For startups, the borrower does not need a physical asset to build a collateral-like structure — it only needs a predictable future cash flow or a mechanism to create payment priority.

Several models illustrate how this insight is being put to work:

The beauty of these models lies in their ability to combine higher recoverability with lower origination friction, alleviating cost of acquisition and risk pressures. Traditional secured lending in SEA is plagued by weak collateral enforcement, slow legal recourse, and informal asset ownership. Proxy-collateral models sidestep these constraints while achieving similar economic protections — making them more scalable and better suited for digital ecosystems.

Furthermore, these models are increasingly attractive to institutional debt investors. As these products mature and deliver stable cash flows with measurable loss rates, securitization becomes viable. Already, we're seeing early moves toward loan warehousing and SPV financing models, enabling FinTechs to scale capital-light. This is where FinTech lending in SEA begins to look more like structured credit in developed markets — efficient, data-driven, and institutionally investible.

These emerging practices are gaining traction not only because they improve credit structuring, but also due to growing regulatory acceptance. In the Philippines, for example, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has opened the door for alternative credit structures through its regulatory sandbox, allowing pilots in loan tokenization, data-driven credit scoring, and platform-led syndication. This signals an encouraging environment for proxy-collateralized lending to mature in the region.

As Southeast Asia’s lending ecosystem matures, the center of gravity is shifting. The early playbook of direct, unsecured consumer lending is being steadily replaced by a new wave of FinTechs building around collateral, data analytics, and institutional-grade capital formation.

B2B FinTechs are becoming central actors in unlocking SME productivity through trade finance, revenue-based lending, and invoice factoring.

At the same time, the rise of proxy-collateralized lending models — enabled by digital platforms and securitization rails — is transforming how credit is distributed and priced in Southeast Asia. These are not just technical evolutions, but represent a structural evolution of the region’s risk capital ecosystem.

For FinTech builders and investors, the road ahead lies in bridging the old and new: embedding financial services deeper into supply chains, partnering with capital market players, and working closely with regulators to balance innovation and protection.